This extra day in February this leap year of 2020 has given me the chance to reflect and document some of the ways I have celebrated Black History Month. As a librarian, I have the authority, capacity, position and responsibility to make access to a broad collection of materials available to a wide base of users. I do not take my stewardship lightly. As a member of the Black diaspora, there are so many beautiful cultural products I want to celebrate and here I share some of my engagements from this month alone with you. How do you celebrate Black History Month? Share with me in the comments.

0 Comments

I’ve lived in Vermont for just over two years now so I have a *somewhat* informed opinion about the state. Let me tell you about some of its selling points and drawbacks. Below we have a list of positives, neutrals and negatives: Positives

Neutrals

Negatives

In conclusion, I generally feel safe here but rarely engaged outside of work. I find that I have the responsibility of creating whatever culture or event I want to see here and it’s burdensome. It is work outside of work. In some other places, like New York City, a subway train ride can bring me close to like-minded people any day of the week and likely at any time of the day. In Los Angeles, we don’t even say we want “Asian” food-- we have the privilege of specifically saying “Thai” and pursuing a variety of price points for that country’s cuisine any. day. of. the. week. However, New York City’s safety record is lower than Vermont’s and Los Angeles’ traffic and parking are epic things of legend. Both of these aforementioned cities have what I’ll call “saturation points” in terms of population that can be suffocating. But I suppose this is a game of “pick your poison”: do you prefer to be under or overwhelmed? Do you want to create culture or live adjacent to it? Do you want to be anonymous or to be known? Depending on what tickles your fancy, Vermont might be your paradise.  You may have noticed that I've been quiet on this blog platform but my voice still resounds! As the Literatures & Cultures Librarian, I've been using Middlebury College platforms for communication. The libraries' blog has allowed me to highlight many voices and discourses:

The Middlebury Campus newspaper has allowed me to author a weekly Fall 2017 column called "The Librarian Is In." And the StoryCorps app continues to allow me to do wonderful things with oral histories. Also, I'm on the libraries' newsletter editorial board. You can see many of the stories I've recruited there, particularly "What Are You Reading & Why?" So, while you may not find the work housed on this platform, it's out there. ;) Stay tuned for my feature in Against the Grain's winter publication for the Up & Comer Award and February's Black History Month oral history series "In Your Own Words."  I’m a two-time “alumna” of the Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) Fellowship. As a graduate student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, I studied both Brazilian Portuguese and Arabic as a FLAS fellow and I want to tell students at the University of Wisconsin at Madison about my experiences through a series of testimonial insights as you prepare your application for this competitive award. Before I begin, I have to say my experience was incredibly positive with just a few (but significant) bumps in the road and I would absolutely do it again. So, I’m irreparably and blatantly biased. Also, our campus has an extensive list of frequently asked questions (FAQs) about the FLAS award that you should definitely review in detail. To find out more about me, see my welcome interview, my resident of the month post, or my personal website, www.katleespe.com. FLAS, the essentials:

Undergraduates and graduates are eligible for this award. While the amounts of the stipends for undergraduates and graduates differ, the FLAS award is available for both groups. For graduate students, the output produced for upper level courses may be lengthier and their proposals for research in their applications may be more detailed. Historically, awards are given with priority for less commonly taught languages. Farsi, Hausa, Igbo, Quechua, Turkish, Wolof, Yoruba, and Zulu are all examples of “less commonly taught languages.” However, it is also possible to study Western European languages in conjunction with this award. You can apply for the FLAS award before entering your degree program. If you know that the study of a foreign language is essential to your success/field/discipline/career before starting your degree program, consider preparing your FLAS application alongside and in addition to your admittance application. I was in graduate school for library science for three years; two of them were supported by the FLAS award. Had I known beforehand about the FLAS and that I was eligible to apply, I may have found financial support for all three years via this venue. As an awardee, you are obligated to take two courses. One of the more obvious requirements for participation in FLAS is that you take two courses: one in language and one in area studies. The language courses are usually easy to identify and the area studies courses tend to span a wide breadth of topics. For example, for Brazilian Portuguese, you may be able to take a dance class in capoeira, a religion class on candomble, or an independent study on the literature of Luis Fernando Veríssimo, the last of these being one of the options I chose. Consult your advisor on your schedule every semester to make sure that you are complying with the requirements of the award. You may need to get voted up. Your personal statement should be compelling and you will likely need your home department’s support/nomination/corroboration. In my experience at Illinois, the first time I applied for the FLAS award, my department was required to collect the application materials belonging to everyone in my field and then rank them before they were submitted to the different cultural centers on campus for evaluation. In any scenario, whether this is the format of the process in your department or not, your department should be made aware of your intent to apply. I suggest multiple rounds of feedback on your statement of purpose between you and your advisor/recommender to make for a strong application. The award is contingent upon approved, federal funding. At Illinois, cultural departments which serve as FLAS-awarding bodies must re-apply for funding every four years. That means that a department may have been an awarding body for five cycles of four-year periods for a total of 20 years but has the potential to lose its funding the sixth time it applies. So, the cultural department that was an awarding body last year, may not be one next year. Moreover, if there are any delays in approval of funds on the federal level, there will also be delays in disbursements. In 2014, the first payments for the award were delayed for at least two months and awardees had to find alternative methods for covering expenses in September and October until the issues were resolved. A larger lump sum was eventually disbursed to make up for lost time, but the situation was stressful for all involved-- students and coordinators alike. It is awarded exclusively by public university campuses. Again, the FLAS is a federal award. It is one of the ways that our country invests in its people to create a populace this is more culturally aware and able to meaningfully engage with people, texts, histories, sciences, et al all over the globe. Private schools cannot select and/or distribute these federal funds to students. However, for example, a student from a private school can apply for a summer FLAS award to be carried out on a public campus or through a public campus’ study abroad program. And, in the case of Middlebury College, a private school in Vermont, awardees from public schools can use their awards on a private campus to study language. In the latter scenario, the student is paid the monies through his/her home institution and then pays a tuition bill to the college. Any program, domestic or abroad/overseas, must comply with a minimum amount of contact hours. Your FLAS award coordinator can give you the details on the stipulations. You can hold the award and earn a wage. Typically, the award does not exclude you from working and earning a paid wage. It may limit the amount of hours you can work per week, however. As a student, I worked as a graduate assistant both years that I participated in FLAS. The two different departments that awarded me the FLAS had different policies on the amount of time I was allowed to work. One limited me to 10 hours a week; another allowed me to work more than 20. Attentively investigate the ways you need to comply with the requirements of your award. Beyond moderating your work hours, you may also need to attend an awards ceremony and/or give a presentation. You will certainly need to have your skill level evaluated at the beginning and the end of your award. Be strategic in planning your "time to degree." If you enroll in a two-year master program, for example, your home university wants to support you in completing your degree in an efficient amount of time. However, you should know that accepting the FLAS award means enrolling in two courses beyond your degree’s requirements every semester for which you hold the award. So, you should expect a packed schedule. With mindful planning, and perhaps even a summer term of courses, you can complete your degree “on time” but know that your study time will likely be intensified by being a FLAS recipient. Academic year and summer awards are separate entities. You can apply for the academic year award or the summer award or both. You may be awarded one, both, or neither. Summer awards are sometimes more competitive as that period may be attractive to researchers wanting to go abroad and fewer awards are granted then. See the FAQs that provide information on what prior experience makes you eligible for a summer award. The government is interested in your progress. You must provide the U.S. government with progress reports that detail how you have used the language for 10 years following the award (even if you have not used the language studied for professional purposes or at all). This means that the federal government will contact you and ask you to respond to questions that pertain to your employment and other professional activities. Awarded funds not used for the purposes intended must be refunded. Between studying Portuguese and Arabic, I made a brief attempt at Swahili. For those of you considering the same, let me say that my change of heart had nothing at all to do with the difficulty of the language. Rather, there were some logistical problems I encountered. Back in summer 2015, there was a mass glitch that “shut down the visa application process” (Yuki Noguchi) and which delayed my instructor’s arrival to the United States by two weeks for an intensive summer course. That means that some 40 hours of class meetings were conducted through Skype. So, while one of two disbursements of the award had been made to me, my decision to drop the class obligated me to return the monies afforded for that purpose. It is a competition. FLAS awards are hardly automatic or guaranteed. Assume that the most eligible, diligent, and interested parties on your campus are applying for this award. They are shaping statements that describe why their plans of study are compelling, necessary, and meritorious. Therefore, your application should be professional, well thought out, punctual, and pertinent to the research needs in your field. Sometimes there’s a second round. On occasion, if a cultural center cannot award all of its funds to eligible candidates on its first attempt, a second call for applications can be made. The cultural centers want to use the funds they are allocated to demonstrate the robustness of their programs and to increase the likelihood of future funding. This means that each cultural center must demonstrate that there is a demand for the languages and courses being taught underneath its auspices. Good luck out there!  I'm working with a comparative literature professor, Dr. Vinay Dharwadker, at the University of Wisconsin at Madison to prepare the Blowtorch Reading Series. It consists of public meetings held on the 8th of every month in which texts that reassert atemporal values are read. They are are read on the 8th of every month in response to the 2016 election. We've had one meeting thus far and there I read three works: I Want a Dyke for President by Zoe Leonard, The Unknown Citizen by W.H. Auden and Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing by James Weldon Johnson. Following this encounter, I have encouraged Vinay to hold these meetings within library spaces. He, in turn, encouraged me, to keep writing. We thought, together, about works that might be appropriate for Black History Month in February and Women's History Month in March. Something inspired by Gil Scott-Heron's 1970 The Revolution Will Not Be Televised was born from these conversations. An original draft: The Resistance Will Not Be Tweeted with all my love to the Holy Gil Scott Heron You will not be able to like this status, “Brah” You will not be able to favorite, vote up, or double tap. You will not be able to share it in a private message, Or tag me in your outrage. Because the resistance will not be tweeted. The resistance will not be tweeted. The resistance will not be brought to you by our sponsor, Posted on Facebook or in convenient, consumable, 2-minute-long video clips. The resistance will not show you pictures of a blighted Aleppo, Burning, crumbling, falling at a boogeyman’s hands, Or bloodied little boys, parentless, awaiting care in an ambulance. The resistance will not be tweeted. The resistance will not be brought to you by Fox News, NPR, or the Atlantic. It will not star Ta-Nehisi Coates, Dylan Moore, or Shaun King. The resistance will not bring you closer to the thigh gap. The resistance will not give you Kylie Jenner’s plumped lips. The resistance will not be the juice cleanse of your dreams. The resistance will not be tweeted, “Brah.” There will be no pictures of Kim’s derrière, naked or clothed, Or Kanye, babbling, balanced, or a little off. TMZ will not catch the right star at the right time saying the wrong thing. It will not “break the Internet.” It will not nod to white feminism. It will not be “Black Lives Matter” on a wrist band. The resistance will not be tweeted. There will be no cell phone video footage of our hands up, hollering “Don’t Shoot.” There will be no black panthers in leotards at a football stadium slaying. There will be no battered windows or sunken patrol cars. There will be no Lemonade. The Walking Dead, Game of Thrones, and Empire will no longer be so go-damned relevant, And no one will care who wore it better because brown people will be talking to each other, IRL, F2F, TBH AF, YGTI. The resistance will not be tweeted. There will be no urgent reports or strategic shots of “professional protesters” Or hashtag movements from the comfort of your own home. The inauguration will not be washed down with a liquor of your choice. You will not be able to “call your doctor and ask about” benevolent dictatorship. You will not get a push notification on your phone, a GroupOn, or an invite. The resistance will not be tweeted. The resistance will not be bookmarked and saved in your cookies Where you can open a folder and get back to it later. You will not have to worry about Sara sharing it first to your reading group, Dan columbusing this fresh discovery, or Mark mansplaining the ins and outs of reparations. The resistance will not be swallowed with a spoonful of sugar. The resistance will not be taken with a grain of salt. The resistance will not be “the nighttime, sniffling, sneezing, aching, coughing, stuffy head, fever, so you can rest medicine.” The resistance will not be tweeted, will not be tweeted, will not be tweeted, will not be tweeted. The resistance will not be favorited, “Brah.” The resistance will be between you and me.  This piece is mostly designed for the college-educated Westerner planning a trip to Dakar. I hereby acknowledge our shared privilege. Moreover, I must say that it is hard to write about a culture not your own with respect, humility, honesty, subjectivity, and objectivity. I’m sure I both succeed and fail below. Picking up where Anthony Bourdain recently left off, let me tell you about some things I noticed during my 8-week stay in this West African city. I should tell you that my experience included a homestay living arrangement with a Senegalese family, so the more typical tourist experience of hotels and hostels does not apply here. Also, I did not go to see the beaches; I went to participate in a brief, professional opportunity, so I got to see a face of Dakar that not many international travelers experience. 1. Dakar is not Senegal and Senegal is not Dakar. Just as Omaha is not the United States, and Helsinki is not Europe, Dakar, despite being the capital city, is not entirely representative of Senegal. Its one million people are situated on the coast, attracted by educational, employment, and commercial opportunities; yet, many residents come from villages and maintain close ties with their families and relatives who remain in more rural areas. 2. Wolof is king. You speak French? Your textbook told you that Senegal was a French-speaking nation? You’ve been working on your verb tables? Je travaille, tu travailles, il travaille? Pff! Yes—the dakarois speak French, but not because they want to, per se. French is/was a colonial language and most people you will encounter have a formidable level of French. However, French is hardly the “default” language of the people. When you come across two buddies sharing tea, overhear neighbors on the bus chatting, or when your host mom calls her son from another room, Wolof reigns supreme. And if not Wolof, perhaps Serer or Pular. French is rarely the language of discourse between people sharing an intimate relationship. French is used in more formal, administrative, and clerical situations. So be sure to look up even some basic phrases in Wolof before arriving. 3. You are a walking dollar sign. Or euro sign or pound sign or yen sign or sign for any foreign currency that is stronger than the West African CFA franc at any given time. This means that taxi drivers, vendors at tourist sites, and panhandlers will intentionally target you for making their next fare/sale/dollar/coin. The attention can be overwhelming. Taxi drivers will put their cars in reverse to pursue you and honk their horns so as not to miss your fare. Beggars will shake their metal tins at you and say “Sa.” And vendors and tour guides on Gorée will hound you with, “Is it your first time? Come see me. My store is at the bottom of the hill. Don’t forget!” (Can you blame them? Money is hard to come by all over the world and it is not any easier in a developing nation.) Moreover-- and I hate to say it-- but ladies, the attention that you receive from men may not be about you but rather the countries and opportunities you have access to via green cards. Any relationship you pursue should be approached with great discernment. Edit: It was brought to my attention that women can be just as opportunistic as men in approaching romantic relationships. That is, it is just as easily true that a woman seeking a chance to 'access the West' has the capacity to emotionally manipulate a man as a man does a woman. Point noted. 4. Islam will inform your days whether you are religious or not. You remember reading about the five pillars of Islam. One of these pillars is salat (prayer) and it happens five times a day. You will hear the call to prayer; you will see Senegalese Muslims bowing in prayer indoors and out; you will wait to have a meeting with someone until s/he is done with his/her ablutions and prostrations. In some way or another, the Islamic religion will touch your life by your mere presence in the city. Despite all the hype, I must assert that it is entirely inoffensive, but ultimately still present and pervasive. 5. The food is good, but repetitive. You will eat the national dish, che bu jen (also known as thieboudienne, in French), a rice and fish dish served with eggplant, carrot, and cabbage. And you will eat yassa, a chicken and rice dish accompanied by a generous amount of glazed onions. Then you will eat them again. And again. Unlike many metropolitan hubs in the U.S., sushi on Monday, tacos on Tuesday, and makhni on Wednesday is not how the Senegalese roll. Variety is not as much of a priority among the dakarois as it is in a heterogeneous society like the United States. 6. Comfort is relative. When you come from a “developed” nation—formerly known as the “first world” and frequently synonymous with “the West” or “the global North”—there are certain comforts you come to expect and take for granted: uninterrupted running water, ubiquitous air conditioning, dependable public transportation, etc. You might want to mark these as “N/A”—“not applicable”—for many places in the global South. Water requires stable infrastructure; air conditioning requires steady electricity; and among other things, transportation requires roads, fuel, safety regulations, and more! While some places can check some of the requirements off the list, not all of them cover everything. So, be prepared to encounter some day-to-day activities that vary from your routine at home: bucket showers, eating in the company of flies, the continuous use of a fan, necessarily dining by candlelight, navigating the stairs with a flashlight, bracing yourself for bumps in the road in lieu of a seatbelt, etc. 7. Transportation is less regulated than it is at home. What does that mean? You may stand next to a bus stop or you may stand by the side of the road and flag down a bus/van driver. There may be plumes of black exhaust exiting multiple vehicles on the road and you and other passersby will inhale it. In a space where three people are intended to sit on your ride, there will be six. While all of these factors—routes, pollutants, and use of space—may be regulated by law at home, that is not necessarily the case in Dakar and/or in many parts of the developing world. 8. Buying from corporate vendors and street vendors are different experiences. When you go to a supermarket in Dakar, for example, City Dia, you can expect air conditioning, a plastic cart on wheels, aisles, and lines. This is much like our experience in the West. However, many Senegalese people visit open air markets to purchase their food products and other wares. In the open air markets, you will see freshly killed and plucked chickens on display, a wide variety of vegetables, beauty supplies, and jewelers. In the corporate markets, one thing you will be asked many times when making a purchase with any bills valued at more than 2.000 CFAs (~$3+), is “Do you have change?” Cashiers appear to make an effort to conserve their coins and small bills and will ask you to help them in that effort. Moreover, cashiers are likely to round up and down in providing change. If you make a purchase for 2000,50 and only have 2000 CFAs on you in cash, the cashier is likely to look the other way as the ,50 is inconsequential. But remember this works both ways. If you make a purchase for 4.950 and pay with a 5.000 CFA bill, don’t wait around for your change. While prices are fixed in the corporate model markets, negotiation (also known as “haggling”) in open air markets and many boutiques is expected. It is your job to suggest an asking price for an item and for the vendor to object saying the amount you propose is too little. Eventually the two of you will come to an agreement. The practice is not for the shy and/or faint of heart. A tip? If you feel a vendor is exaggerating or asking too much, walking away is extremely effective. 9. Laundry. My household consistently had hired help in the house. However, for washing clothes, a team of laundresses were invited in every fortnight and hired to wash clothes by hand. They arrived before 8:00 a.m. and went about washing the family’s outer garments in large plastic tubs of water the regular maid had collected the night before. After rinsing, the laundresses hung the clothes out to dry; then they ironed the clothes and folded them. They left the house around the lunch hour, some four or five hours later. The labor is intense. If you don’t want to cross these ladies, be sure to keep your underwear and socks out of the piles to be washed as everyone washes his/her undergarments by hand him or herself. 10. The talibés. “Talibé” is a word of Arabic origin that means “student.” In Senegal, it refers to young boys, aged perhaps four to twelve who walk the streets asking for money to finance their Islamic instruction. They say “sa” and often carry metal pots to receive and store any change given to them. Theoretically, they are under the instruction of a “marabout,” a religious leader and teacher that will instruct them in reading the Koran and guide their religious maturation. Legislation is being formatted to ban, limit, and/or reduce this practice. However, finding proper alternative education and systems is clearly not easy. 11. Colorism is real. Colorism is an international phenomenon that almost exclusively gives preferential status to people who have “white” or light skin. The legacies of colonialism, slavery, and long-standing socio-economic hierarchies based on caste systems all reinforce colorism. The system of promoting and valuing light skin has a real impact all over the world, Senegal included. You can see this favoring of light skin manifested frequently on television programs. For example, if a woman is reporting the news or playing the love interest on a sitcom or soap opera, her skin often reflects a shade that would pass the infamous “brown paper bag test,” despite the fact that the overwhelming majority of women in the country have rich, deeply dark, ebony skin. Colorism has led to the widespread use of skin lightening products that are damaging to one’s health. These products are most often used by women and are theoretically believed to help them attract suitors and to secure a greater social status. Again, products such as these are used throughout the black diaspora, in South Asia, and throughout the world. 12. Tailor-made clothing. While in the West we are accustomed to buying clothing that is “ready-to-wear,” many Senegalese seek out “tissu” or fabric for making clothes and then visit a tailor who takes their measurements and creates custom-made garments. Many a boubou is made this way. The good? The fit of one’s garments will be extraordinary. The bad? As you buy the fabric in meters, you may end up with more than you want. However, there are many creative ways to make use of the excess: head wraps, decoration for earrings and shoes, tablecloths, napkins, tapestries etc. 13. Sharing is a default orientation. In the U.S., where we are very individualistic, we tend to expect there to be a policy of “What’s mine is mine and what’s yours is yours.” Among the Senegalese, one might say, “What’s ours is ours.” So, if I bought a Kit-Kat or an orange, I expected to share it with anyone who was in my vicinity. It was a pleasure to do so, something that made me feel more like a family member and friend. However, when I stored drinks in the refrigerator to have something cool for later and they disappeared, my pleasure was somewhat abated. 14. Eating out is not as prized as it is in the West. I’m crazy about a diversity of foods. However, I can’t prepare all the varieties of foods I love expertly at home. So, in the U.S., eating out is a large part of my life. This is not the case in Senegal. Restaurants are expensive and frequented, often, by people who either do not know how to cook, do not have a spouse or maid preparing meals, or who are transient/ temporarily in a metropolitan space. While you hear phrases like this one all the time in the U.S., “Did you hear about that new place on 5th Street? I hear they serve Hawaiian fusion tacos. I can’t wait to go!,” I didn’t hear anything akin to that at any time while in Dakar. 15. Blackouts and water cuts. For the two months I was in Dakar, I experienced about four blackouts. Two happened while I was at work; two happened while I was at home. The first lasted about three hours; the last lasted about fifteen hours. Work productivity can come to a halt, particularly without Internet access, and the comfort you once felt from your fan can soon become discomfort in its absence. Nonetheless, while the blackouts were unpredictable, they were also infrequent. Regular access to water was more of a challenge. I lived high up on the third floor of a single-family home along with five other, international boarders. While I had my own bathroom, water ran sporadically, more in the evening, and less during the day. So, it was a regular practice for all six of us to collect water, from one shared spout, for cooking, laundering, and showering. My showers so regularly involved buckets and a cup that at some point, I stopped even testing the tap to see if water would come out of the shower head. 16. Teranga is real. “Teranga” is the word used for Senegalese hospitality and, for me, it is befitting as the Senegalese give with open hands. Maybe I should rephrase that. The Senegalese are not giving away all of their material possessions left and right. They give their time, energy, attention, company, and humor most often. For my first weekend in Dakar, my supervisor left her daughters with a relative and accompanied me to Gorée Island as I’d never been and knew no one in the country. I was invited on multiple occasions to a friend’s home to break the Ramadan fast and dine with him and his family. A library patron of mine invited me to her home and prepared mafe, a peanut butter stew dish, for me; then her father bought us grapes and mangoes and paid for my cab fare home. While there, I encountered impressive displays of generosity, some I would not necessarily expect from my own family. 17. Ataya is the best. Literally, ataya refers to a strong brew of hot green tea served in glass shot glasses, but it is actually quite a bit more than that. It is an event, a tradition, a ceremony, a break, a pause, a gathering, a coming together, a demonstration of presence, nearness, intimacy, and friendship. The tea is attentively prepared and served in multiple rounds after lunch and/or dinner. It is mixed dramatically with long pours (not spoons) and generous amounts of sugar. The server offers a glass to everyone in the room, making sure everyone is included. Though every round of ataya only includes a few ounces of beverage for each drinker, much like the sobremesa, the session can last an hour or more as the objective is to be present with one’s peers and/or family members and to discuss whatever may come up. Sharing moments during ataya is one of the most intimate ways to get to know the Senegalese. 18. Senegal is a haven for other Francophone Africans. This may just be a figment of my imagination, but my residence was shared by two men from Madagascar, one from Chad, and another from Burkina Faso. Moreover, the one night I went out dancing, I was accompanied by a group of Cameroonians. Most of these people were pursuing graduate studies at the University of Cheikh Anta Diop. One was working full-time and shaping a start-up. It appears that in comparison to some other Francophone African countries, Senegal offers a stability and hub of opportunity not necessarily found throughout France’s former colonies. 19. The religious tolerance is a true and fair estimation. The idea that the Muslim and Christian populations in Senegal get along and value peace between each other is a popularly touted truth. This is one of the first things you will hear about the Senegalese and it can be easy to dismiss. Yet, if we pause and consider the uniqueness of this phenomenon, we may learn something. There are few places in the world that embrace religious diversity the way the Senegalese do and it is worthy of admiration. 20. Senegal is both traditional and modern. The same woman who made me mafe, covers her hair with a hijab-like scarf everyday. While she made me mafe, she also told me of her admiration of Nicki Minaj and showed me her best twerking dance moves. No, I wasn’t expecting it. My home stay brother, who dressed in traditional clothing on Fridays for the mosque, was obsessed with the latest cell phone technology-- even more than me who has heightened access to these technological toys-- and LeBron James. I was asked at least five different times if I had What’s App, a tool used to remain in conversation with friends while away and abroad. Prominent stereotypes we encounter in the U.S. suggest that anyone who is deeply religious is also antiquated and unable to appreciate the complexities and comforts of the 21st century but the Senegalese consistently prove that this is simply not true. For more on the context of my experience, visit the Hack Library School blog and search for writings by Katrina Spencer in the fall of 2016. Also, see the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Center for African Studies' Fall 2016 Habari Newsletter.  Reproduced from the Glocal Notes blog. On May 4th, I got an e-mail that informed me that my DNA results had been processed and were available for review. I was nervous, almost as you might be in anticipating the results of an exam, and anxious, like when you’re sitting in reception, waiting to be called in for an interview. Would I ‘pass’? Was I ‘good enough? Would I find out information I in fact not want to know? I logged into Ancestry DNA, and the image above depicts what I found. Eighty-one percent of my ancestry stems from West Africa, including people in regions that reside today in Benin, Togo, Nigeria, Cameroon, Congo, Senegal, Ivory Coast and Ghana. Also, nineteen percent of my ancestry is European, the largest region represented being Great Britain. The image is a recipe, in a sense, for who I am. I have generous helpings of the French and English-speaking African Gulf and a pinch of the United Kingdom. This data represents my ethnic background and I felt myself walking taller and prouder as I began to process what this new information meant. Wanting more from my latest revelation, I began to seek out people I trusted who were also of African descent to help me to make sense of my findings. Did this data merely confirm what I suspected all along? Or was there more to it? My investigation led me not only to amplify how ideas of identity and ancestry are interpreted, but also to uncover some of my own biases. I interviewed a series of people who helped me to understand the diversity of perspectives related to heritage and some of their nuances within. The first of these was Dr. Assata Zerai. She’s an associate dean in the Graduate College, a sociology professor and the new, incoming director of the Center for African Studies. Like me, she is African American, having been born and raised here in the United States, and shares not only the legacy of slavery, but also common phenotypic markers of Sub-Saharan African ancestry: brown skin, highly textured hair and full lips. When I asked her if she had ever considered requesting a DNA test like mine, her response was, “Not really.” As a self-identified Pan-Africanist, acknowledging a connection to the continent and its diaspora was more of a priority to her than knowing what specific regions represented her ancestry. Dr. Zerai’s research, professorship and mentoring, after all, regularly engage discourses regarding black populations. Some of her forthcoming publications, for example, address questions of healthcare in Nigeria, clean water in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda and masculinity in Zimbabwe. For her, blackness is not necessarily something one verifies via chromosome counts and markers; it can manifest itself as a lifestyle through the people she cares for, the investigation she pursues and the scholarship she intentionally engages. For her, the likelihood of laboratory results meaningfully impacting the path she has already chosen is low. In the same effort of accessing my community to help me to interpret my results, I sought out Victor Jones, the Visiting Recruiting Specialist in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science. Victor is from the Southside of Chicago, and, aside from being a professional wrestler and a major R&B aficionado, he is also a Christian minister. The preservation of the black family is a continual concern for him and encouraging young people towards higher education is an integral part of his work. Interestingly, Victor says, “I don’t call myself African American. I prefer ‘black.’ I can’t readily trace my roots back to Africa.” Moreover, if any visit to Africa involves exposure to extremely high temperatures or sleeping under mosquito nets, he is simply not interested. “I don’t want to be outside of my comfort zone,” he said, claiming he would never live abroad. It was perhaps here that I began to realize that there were some myths in my mind that I had not yet confronted. Having spent the last 13 years on college campuses, I blindly believed that everyone wanted to go abroad and that the major obstacles were the price of plane tickets and short-lived vacation time. Learning that someone I knew opted to pass on opportunities to see the world stopped me and caused me to check my assumptions. While the African continent represents part of our shared historical past, the need to intimately know it is not necessarily pressing to all black peoples. For Victor, ministering to local populations and creating strong, reliable bonds with them takes precedence over international travel. These two interactions reinforced the ideas that not only do African Americans—or blacks, depending upon one’s self-identification—eschew a monolithic set of preferences regarding what we call ourselves, but also the lack of information regarding our heritage do not necessarily make members of these groups feel less than whole. Some African American people are satisfied with their identities within a the U.S. context. And, beyond that, a narrative that begins with slavery in North America is not necessarily a problematic one for those who ascribe to it. While understanding that there is an inextricable link to the “Motherland,” there is also a rich history and arguably separate identity here within the United States. Who am I to suggest otherwise? My reaching back into the annals (or lack thereof) of history in a search for self is just as valid as those who reach out and around them for the same purpose. My interviews, however, did not stop there. I wanted to get some feedback from some people who came from African countries. Surely their experiences were different and therefore their opinions, too. I next spoke with Dr. Maimouna Barro who is the Associate Director of the Center for African Studies. She teaches a course called Introduction to Modern Africa and, after making wudu (an Islamic cleansing ritual) and completing her afternoon prayers, she relayed to me her thoughts on seeking ancestry. While Senegal is the place she calls home, she clarified that “If you dig deeper, I’m not just from Senegal.” She then gave me a brief, multi-generational genealogy that included places of origin like Guinea-Conkary and Mauritania. These revelations highlighted another gap in my thinking. For example, if an ethnic group moves from home to a new site, much like with the displacement of Native American tribes along the Oregon Trail, are place markers a reliable source of ethnic identity? For example, I was born in Los Angeles, but that tells nothing of my father’s immigration from Costa Rica and my mother’s family’s migration from Louisiana or anything about our ethnic identities. So what does it mean, then, to submit one’s DNA to a laboratory and to pay for a map that matches one to places? Do we not really want a match to people? Not the imaginary boundaries we have assigned to land? Thomas Mukonde, a Zambian graduate assistant in the Undergraduate Library who works in both reference and instruction, was my last interviewee. He said that while tracing DNA seemed interesting, he would have to justify the cost. He knows, for example, that his parents represent the Mambwe/Lungu and Bemba ethnic groups and stated that he does not have a full need to explore his background as someone who is African American might. Moreover, based on his experiences as an undergraduate in Washington, D.C., he found that attempts to connect the African and African American student communities did not fully develop. “The only thing that unifies us is a history of oppression,” he said. “Africans in Africa were colonized. They were deliberately educated to become subjects or citizens. These education systems were very efficient. I don’t know how much Africa remains in the Africans who stayed on the continent.” Thomas suspected that within African American communities, despite and amidst centuries of deep repression, there was a preservation of African customs. Yet, history may have been overly effective in erasing some of these cultural manifestations on the African continent. As with all of my intellectual inquiries, Project Genesis has brought me more questions and conversations than answers. What I found, however, was that at the same time that I was trying to dispel myths, I was working from a space of assertions I assumed to be true, and my investigation continually challenged them. How do I feel about my results? I was surprised that Benin and Togo factored in at all because in my mind, I had mistakenly ‘othered’ the regions as they are Francophone and not Anglophone; I was expecting a large swath of my ancestry to be West African, and I was right; I had an inkling that part of me was Nigerian, and that was correct; I was also a little disappointed to not have any Native American group show up in my results as my family lore suggested, as it does in many African American families, that we shared a lineage with some group(s) indigenous to the Americas. Some lingering queries address my siblings: If they were to submit DNA samples, would their results be identical to mine? If I am 19% British, does that mean I’m white? Were I to ‘return’ to West Africa, what would await me there? This process taught me anew that the words ‘history’ and ‘identity’ more often than not should take on plural forms, and also that speaking to trusted people is key to finding one’s truth. For more sources for research on black ancestry, as recommended by the interviewees in this article, see the list below. Below you will find an advertisement for a course led by David Wright that explores some of the same issues raised in this piece. Click here on Project Genesis: The Quest to see the first half of this series and be sure to like the International and Area Studies Library’s Facebook page for more articles like these. The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin Black Feminist Thought by Patricia Hill Collins The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. DuBois Out of One, Many Africas: Reconstructing the Study and Meaning of Africa by William G. William and Michael O. West How to Be Black by Baratunde Thurston The Mis-Education of the Negro by Carter Godwin Woodson Slavery and Social Death by Orlando Patterson  It all started in 2006 when Harvard professor Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. made a documentary series about tracing one’s roots to Africa. I thought, “Oh, that’d be nice to know.” Like the overwhelming majority of African Americans, I don’t know where exactly my ancestors come from on the African continent of 54 countries just across the Atlantic Ocean. Despite my interest in pursuing my query, I wasn’t prepared to put any money behind my curiosity. Then last year, CNN anchor Michaela Pereira joined the quest, traveling to Jamaica and publishing the story of discovering her roots. This was another, welcome reminder of something I intended to get back to. I was only convinced, however, when other African American, U of I graduate students like myself, LaKisha David and Jarai Carter, told me that they, too, had participated. They’d sent their DNA samples into laboratories and gotten better, more reliable clues about their places of origin. So, when I had enough money, I decided to join them on the journey, too. African American history is complicated. Not only does an expansive ocean stand between me and Africa, but also a few centuries of slavery. As you might imagine, because many records have been lost or were never kept, beyond my grandparents’ generation, genealogical lineages are rather blurry. It’s near impossible to not feel a sense of loss because of this. Yet, history, as it is wont to do, and biology, too, offer suggestive remnants that lend some clues about the past. For example, I know my mother’s mother is from Louisiana, so I assume my matrilineal lineage traces back to that Southern state. Moreover, my mother’s fair skin and hazel eyes seem to suggest a European ancestor. My father’s skin is a deep brown and he comes from the English-speaking Afro-Costa Ricans of the Atlantic Coast. While I’m pretty certain his great-grandparents were Jamaican, I don’t know where they came from before that. So this is how Project Genesis was born. It entails my effort to employ the DNA-tracking services offered by ancestry.com to determine greater specificities about who I am and to document the process so others who choose to pursue a similar route can form realistic expectations of the experience. On March 14, 2015, I paid $99.57 for an ancestryDNA kit. It arrived on my doorstep on March 21. It came in a little white and green box, not much larger than the palm of my hand, and inside there were two tubes—one was for collecting my saliva, and another containing a blue stabilizing solution for the DNA sample. It will take a minimum of six weeks before I get my results. Before we label these services, however, as an “answer-call, cure-all” when it comes to questions of African American identity, origin and belonging, let me share some of the research I did before embarking on this adventure which truly taught me to temper my expectations. After speaking with LaKisha and Jarai about their experiences, I learned that this test, like any other, has its limitations and therefore must be contextualized, specifying what it can and cannot do. LaKisha is a Ph.D. student in Urban and Regional Planning who is in her thirties. She has spent some $800 with three different services in order to have her and her family members’ DNA tested. Collectively, the services were carried out by ancestryDNA, 23andme and African Ancestry. LaKisha freely admits that each service has its plusses and minuses. As she describes it, what the test attempts to do is to match one’s DNA to a database of DNA that is already held. That is, it tries to match one’s DNA to a group of people that is currently alive today. The crux is that in order to be effectively matched, the database needs to be rather comprehensive. For example, if no tests were conducted for the people living, say, along the coast of the Gambia, it’s impossible to have a result yield a reliable match to that particular population. “Do not do this test if you are looking for a place of origin,” she cautions. The results provide a map that highlights the countries where one’s DNA has resonance. In Lakisha’s case, (and Raven Symone’s), multiple countries are highlighted: Cameroon, Gabon, Nigeria, et al. So, in this case, when five to ten places show up as matches, the results aren’t as conclusive as one could hope. As a matter of fact, the test seems perhaps most helpful in telling one where he or she is not from: the Maghreb*, East and Southern Africa, for example. However, that information based on history alone may already be evident to us. The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade we know was primarily carried out along the coast of West Africa. Is it worth it to pay $100 to have a test confirm that, yes, African Americans are indeed of mixed West African descent? It would appear that the novel information provided pertains to one’s ancestry that is not African. LaKisha’s background, for example, included results that were 87% African, 5% Native American and 4% European, and this is where LaKisha offers some advice: “It might be more effective to have your oldest living relative tested.” This way, the expectation would be for fewer countries to be named in the results as the oldest relative is closer to the source of origin. Also, she says, the more African people who take the test, the more accurate results will be. However, what motivation does a Senegalese woman living in Senegal within her Senegalese community have to take a test that costs $100 and ultimately tells her that she is Senegalese? “But do you see the potential?” LaKisha asked. There’s potential, but the process may not be practical. Asking African people to submit their DNA to a database so African Americans can know more about themselves may simply be asking a lot. After carrying out African Ancestry’s Patriclan test on an older, male relative, LaKisha learned that her lineage was traced to the Akele people of Gabon. This information appeared on one document and specified which of her relative’s chromosomes indicated the connection. What this sheet of paper didn’t do was provide the names of definite familial relatives alive in Africa. It didn’t state how to find other Akele people in the Midwestern, North American region where we currently reside. It also didn’t provide a profile on the Akele that showed them to be nomadic people or urban dwellers, tall and sinewy or short and slight or patriarchal or matriarchal. There is a real risk, then, in these tests becoming predatory. While the companies profit, do African Americans get the answers and information they seek? While we observe a viable business model, in the end only the faintest inklings of information are provided. I also spoke to Jarai who is a Ph.D. student in informatics and in her twenties. Her results from ancestry.com indicate that 55% of her background is European and 43% is African, which, was not entirely a surprise to her given her mother is a white American and her father is a black American. Her advice? “Don’t do it if you expect to be 100% black,” she said. “There were actually people angry that they have white heritage.” Given the legacy of the slave trade, many African Americans have a mixed heritage that may or may not be perceptible based on their phenotype. The genotype, however, which is what we’re testing, may reveal some unexpected information. Jarai says she was “hoping to find out more about relatives, but only got pointed in a general direction. She admits, too, that the database is limited. However, seeking out this process brought her family together. Lakisha also said that generally hers was a positive experience and is happy to have a starting point for further research. What we all agree on is that this type of adventure can take a lifetime of mapping, digging and testing, and apparently, I’ve signed up for step one. Stay tuned for the second feature in the The Genesis Project series. |

AuthorMy name is Katrina Spencer. I'm a librarian. Archives

February 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

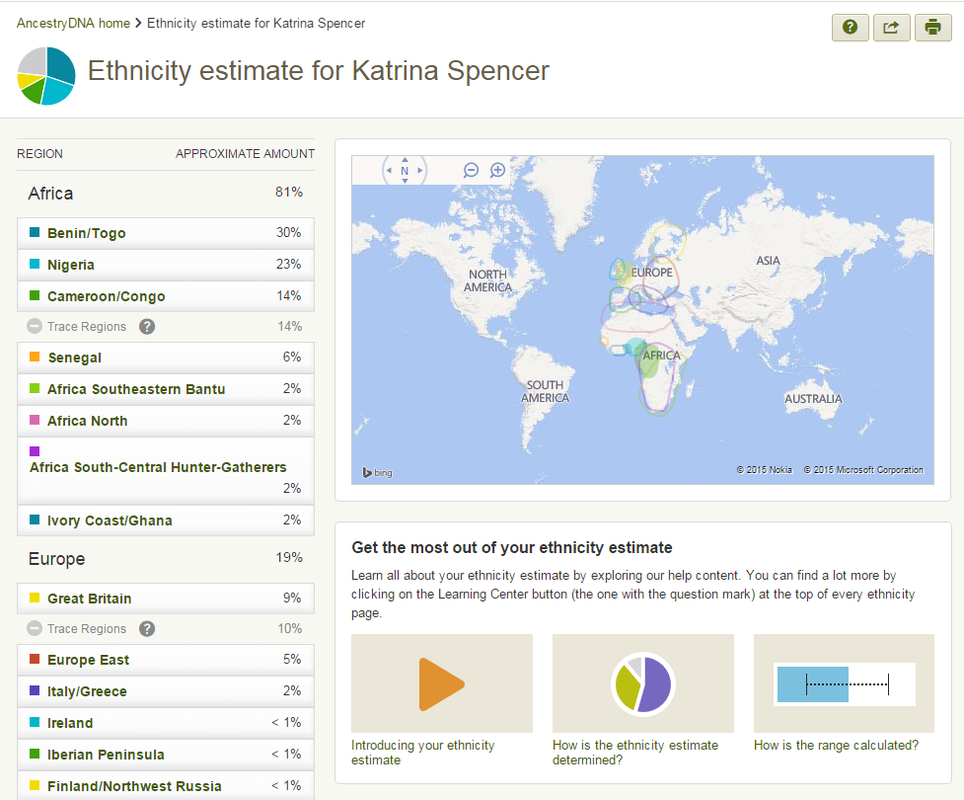

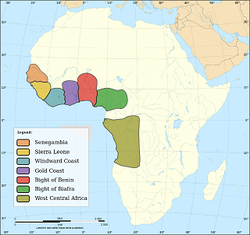

RSS Feed