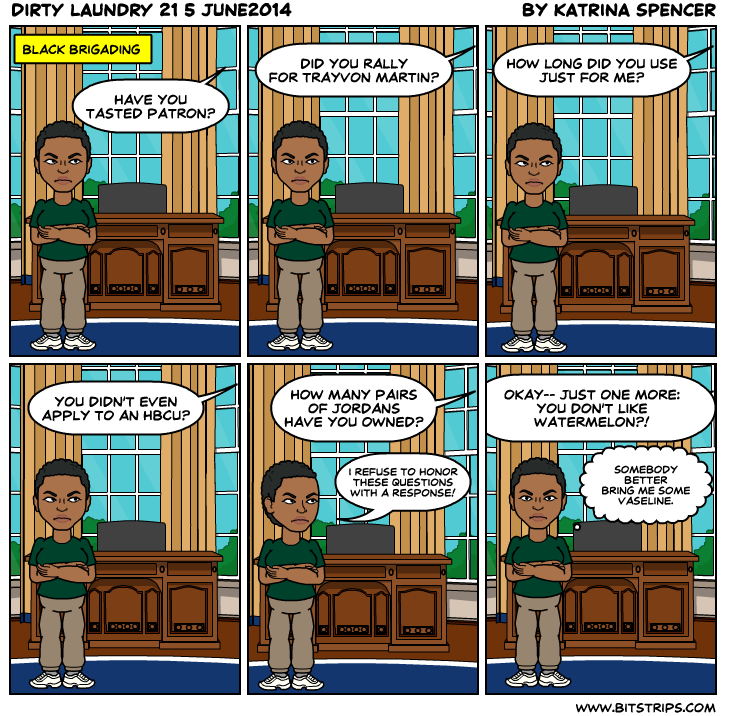

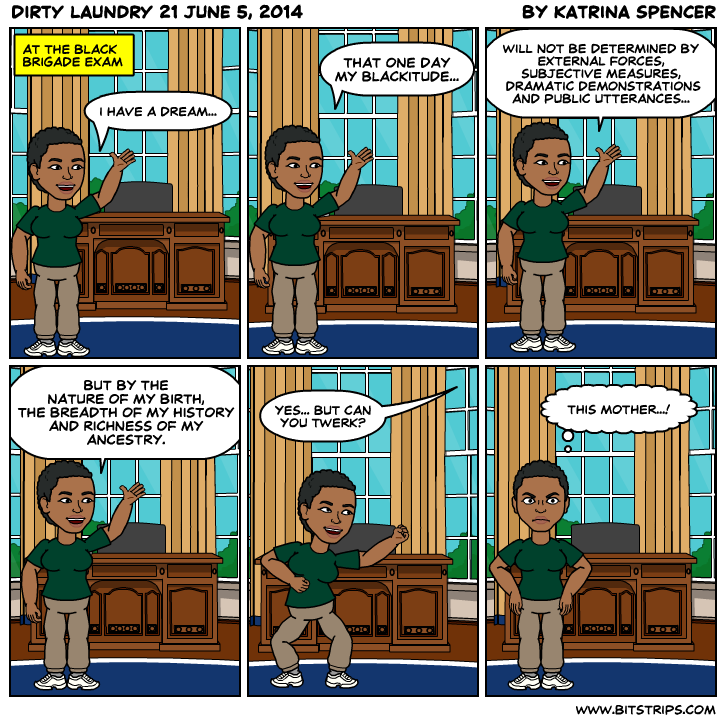

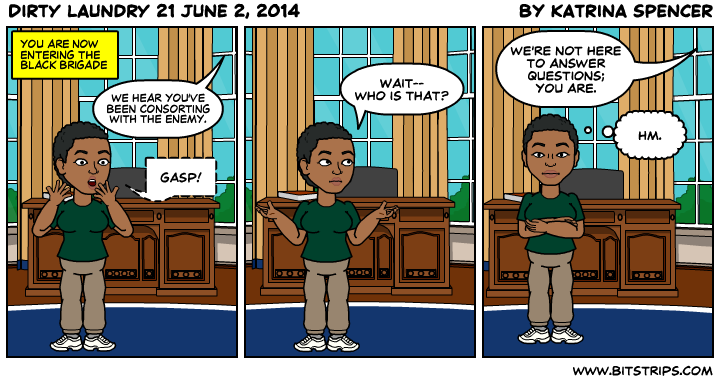

This week I’ve been reading Baratunde (Rafiq) Thurston’s How To Be Black. I first saw it in one of Chicago’s O’Hare bookstores at least 8 months ago but I intentionally did not pick it up because I had another book on my person that I hadn’t finished reading. I didn’t need more weight in my luggage and bags, especially when I had enough reading for one weekend. Now that I’ve got it on interlibrary loan from my campus’ university, I love it. Or I loved it. I loved it when I was flipping and reading the parts that were of immediate interest to me. Then when I started to peruse chronologically, I realized I liked it. What I mean by that is that there seem to be chapters that are geared to my life and this particular phase of it, for example, “How Black Are You?” But, in some places, it’s much more of a memoir than an exegesis on ‘the state of things.’ It’s not bad anywhere; it’s just that sometimes it’s holding up a mirror and at other times, for example in talking about a famed Quaker school called Sidwell, it’s a window. This morning, however, I came across a chapter called “Have You Ever Wanted to Not Be Black?” Thurston interviews a handful of friends/colleagues who are black to get their response. And I paused a bit wondering what my own reply would be. And after 3.5-4 seconds, I realized my answer was, “No.” And therein this blog post was born. I love this new epiphany of mine that we answer the questions that are asked of us. So, here’s to this one: Have you ever wanted to not be black? No. I’ve wanted others to allow me to be black in my own way and to dispel preconceived notions of what that means. But I have never wanted to not be black. I’ve want to run away from the hot comb, Just For Me chemical hair relaxer and time-consuming twist-outs. I’ve wanted to take less time prepping in the morning and lotioning my body. I’ve wanted swimming and sweating to be less of a burden. I’ve wanted to encounter fewer ignorant people like the young man who told me to go back to Africa in the 5th grade. …to stop being associated with loudness, aggression, sexually explicit dance, anger, the violence, gangs and drugs of the inner-city… but no, I’ve never wanted to not be black. Blackness is beautiful. Some of my favorite moments are when my skin is pressed up against that of a dark-skinned man and our bodies look like delicious chocolate and caramel candies. I love the curly definition of my hair (on good hair days). The voluptuous volume of my lips. The womanly curves of my body. The generous symmetry of my nose. And my flirtations with beautiful, African men. The amber shade of my eyes in the sunlight. The freckles on my nose. The Caribbean cuisine in my father’s kitchen. The gumbo in my grandmother’s. The anonymity/fact that I could be from Panama, Puerto Rico or Paraguay and no one would be the wiser. I happen to love giant hoop earrings. R&B, some hip-hop and a dash of neo-soul. Creativity and creation. And curls. Did I mention curls? What I don’t like are · despair · low expectations · willful victimization · the glorification of ignorance · being late · being monolithic · being homogenous · group think · voluntary segregation · inflexibility · having to wear blinders to fit in · no room for dissent or contradiction · watermelon (or cucumbers or PB&J sandwiches or bleu cheese for that matter) · the glorification of a poor ‘n’ deadly diet · turning in assignments late · reading from only one cannon · having the terrain(s) I’m allowed to visit determined by someone other than myself and my loved ones · having what I consume determined by someone other than myself and my loved ones · being told how I feel · being told who I am · being told where my loyalties lie But no, I’ve never not wanted to be black. I’ve always wanted the freedom, however, to determine what blackness means to me. I’ve wanted self-determination and not the U.S.’ dominant culture via the media to tell me what authenticity looks like and feels like or for my peers and perceived ‘community’ to do so. I’ve wanted to only have to answer to Kirk and Notachai Spencer, my progenitors, and to lead a life of humanity [and blackness] that is pleasing to them and God. And so far, I think that [mostly] I’m doing a good job. And then after I wrote this, I read the chapter that motivated my response. Good and similar stuff found therein.

When I started studying Portuguese with Rebeca Coelho in the Fall of 2013, I didn’t expect to encounter comics. Rebeca used a variety of authentic sources to illustrate real language use and A turma da Mônica (Monica’s Gang), by Mauricio de Sousa, Brazil’s most successful comic, caught my attention. Aside from being cute and colorful, it taught me novel uses of the language like puns and in some ways contrasted with my expectations for children’s comics. For example, Monica hit her friends; her friends, Cascão and Cebolinha, who were less than 10-years-old, had overt amorous feelings towards their babysitter; and when a joke’s humor required a boy character to be nude, illustrators did not shy away from including the characters’ genitals. So when the class was instructed to do a cultural project for the semester, something that would focus on something specific to the Lusophone world, I decided to that this series would make for an engaging topic. And it did. I found, however, that I couldn’t speak about Mônica without talking about Charles Schulz and his series, Peanuts. Peanuts was my point of reference for any comic that began in the newspaper and, as my research showed, a worldwide classic beyond U.S. borders. What I noticed was that both of these series had a similar feel. They involved grade-school characters who spent time together playing and discovering the ironies of life. Little attention was paid to adults and their surroundings were generally safe. I noticed, however, that some other comics, published in different periods, while still featuring children, were decidedly more abrasive and political. Aaron McGruder’s The Boondocks was one of them and Alexandre Beck’s Armandinho was another. These two series were admitting themes that resonated far from the playground, among them social injustice, race relations, environmentalism and others. It was around this time that I felt a pressure to formalize my study of these issues. After all, the materials I’d need kept accumulating and who better to direct me than Dr. Carol Tilley, a professor of comics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “Out of the Mouths of Babes” is the preliminary result of my investigation and I share it with you here. The title is of biblical inspiration from Psalm 8:2 and has made its way into popular U.S. vernacular. The phrase is used to express astonishment at wisdom seen in children, the phenomenon I, too, saw in the comics that form the basis of this study. I recommend that you start reading around page 3. And I will say two additional things in conclusion. It was the conversations surrounding these questions and queries that led me to write a strong research proposal for the Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) fellowship and I expect it to be strong fodder as well for a Fulbright. Special thanks to Christine Jenkins, Kathryn LaBarre Amani Ayad and Sharon Irish for their constant votes of support.

Twelve days ago I was formally invited by The American Library Association’s (ALA) Knowledge + Alliance Initiative/Diversity and Spectrum Office via Gwendolyn Prellwitz to go to the University of Illinois at Chicago and provide prospective library and information science students of color with essential information about graduate school life. Several discussions were facilitated and while I was responsible for providing recruits with information regarding funding, resumes and personal statements, my initial inkling was to educate this group on graduate school culture. My assumption (which was generally correct) was that the majority of the audience would be made up of undergraduates. Thusly, I wanted to let them know how the demands of even higher education evolve as studies become more specialized. Below you will find the list of points I shared in a hand-out. But let me say these three things first: (1) I am so pleased that this request was made of me once the Spring semester had been completed. Thank you to Kate Rojas for keeping me in mind and for navigating the city like a pro. (2) Another highlight of the trip was not only in meeting new faces and returning to see familiar ones, but I also got to see new spaces, for example, the Skokie Public Library, a paradise of resources and funding. I am as glad about sharing the knowledge I received as I am about seeing parts of Chicago I hadn’t seen before. (3) For anyone considering coming-- and I mean anyone, regardless of color, please peruse the lib guide called POC @ GSLIS that is in development and intended to serve as a bridge of knowledge as you approach libray and information science (LIS), be it here on our campus in Urbana-Champaign, through LEEP or away at/in/for/with another institution. On the Library and Information Science [LIS] Culture · Independent studies are a thing. · You may never find a more interdisciplinary field. · LIS is the most LGBTQIAA-friendly place I’ve ever seen. · LIS is one of the least racially diverse places I’ve ever seen. · LIS is one of the least gender diverse fields I’ve ever seen. Things You Should Know About Grad School [in General] 1. “Reading” rarely means “reading.” Hundreds of pages of reading will be assigned to you on a weekly basis. The instruction to “read” them usually means ‘become familiar enough with the arguments presented in order to meaningfully engage in a discussion. What it doesn’t mean is ‘read every word, take detailed notes and prepare for a test on the contents.’ Learn to read effectively focusing on titles, authors, dates of publication, topic sentences, introductions and conclusions. 2. You can get straight As and not learn a thing. Grade inflation is rampant in graduate school. But if you’re there to learn professional skills, why not make an effort to pick some up in the process? The objective in graduate school is not a 4.0 GPA. While those grades might make you competitive for awards, fellowships and scholarships, a perfect GPA should not preclude healthy, long-term relationships with peers. Networking is a professional skill. Library and information science is a small and intimate world: the person hiring you tomorrow could be the introverted, bespectacled woman who avoided eye contact and knitted scarves in your required class all last semester. If she invites you to a Makerspace, picnic or workshop, genuinely make an effort to go. 3. Projects and papers no longer end when the semester does. When you create and develop something—be it a line of research or a reference tool like a lib guide—try to envision its lifespan beyond its deadline for class. In other words, strategize ways to make your efforts sustainable. Realize that in-class assignments can also serve as evidence of your professional capacities in “the real world.” 4. Learning is hardly restricted to the classroom. Graduate school is different from undergrad in one of many respects in that you can no longer ‘point at your progress’ as effortlessly. Before perhaps you could point at a test and say ‘I earned an 87%; the 13% I missed is very clear and this is how I can make it up or do better next time.’ In graduate school, where you are surrounded by theory, intellectual debate and burgeoning research, your success will be determined by many other, non-numeric factors. For example:

In other words, the measures of success are entirely different animals and you, not your instructor or supervisor, will be responsible for doing a good deal of evaluation and reflection for yourself. 5. You will have to introduce yourself, present and have speaking points regularly. You might as well get used to it now. This is how you make a space for yourself in academia, by heightening your visibility in as many ways as possible: conferences, symposiums, publications, resources, collaborations, networking, online presence, etc. If you choose to avoid the limelight and invitations to make yourself visible, you will be invisible. 6. The importance of proactivity cannot be overstated. Everything you want you must pursue tirelessly. As some African Americans say, “you gotta be on your grind.” Sometimes you have to hunt down the opportunities you want as though you were earnestly stalking prey. Frequently, if you want to create a space or opportunity, it will imply a grassroots effort that begins from the ground up. There’s no more ‘passing,’ ‘I’m gonna sit this one out’ or ‘let somebody else do it.’ It’s up to you. You get out what you put in. Every effort is an investment that will have its own returns. 7. Not everyone’s going to be in your corner. That goes for professors, peers and everyone in-between. Foster and nurture relationships with people who demonstrate their support of you. Skin color is not going to determine who your allies are. 8. You may not finish with the same cohort you started with. And that may not be a bad thing. While sustained relationships with peers are encouraged, they can’t be the determining factors of your success. If you need an extra semester to take an additional class or an extra year for an awesome practicum or certification, take it. Remember that how long you take to reach the goal is less important than arriving there. 9. Your sedentary lifestyle is likely to lead to weight gain. 10. If you’re looking for a dating pool, don’t bank on it. |

AuthorMy name is Katrina Spencer. I'm a librarian. Archives

February 2020

Categories |

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed